| Detecting HPV |

| HPV DNA testing in clinical practice |

| Immune response |

| Clinical trials and vaccines |

Clinical trials of the HPV Prophylactic vaccines

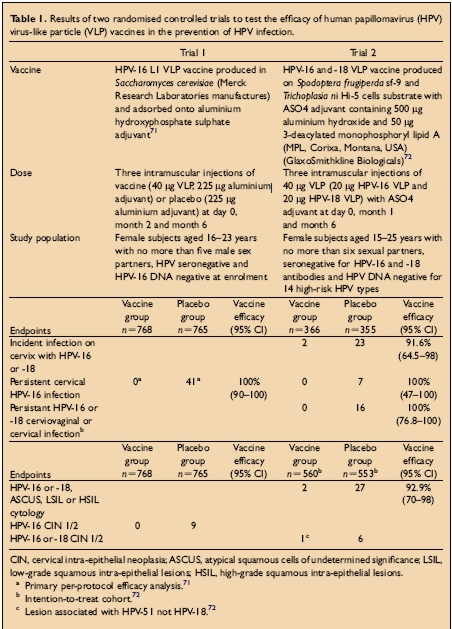

There have been two large double blind randomised controlled clinical trials of papillomavirus vaccines. Both have shown protection from persistent HPV infection and cervical disease with homologous HPV types after immunisation with HPV VLPs. The study population, doses, vaccines used and endpoints for the trial are shown in the Table below:

Williamson et al

Stratergies for the prevention of cervical cancer by human papillomavirus vaccination

Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology (2005) 19-4 pp531-544

Trial 1: Persistent HPV infection defined as the detection of HPV16 DNA in samples obtained at two or more visits

Trial 2: Persistent infection with HPV 16/18 defined as at least two positive PCR assays for the same genotype separated by at least 6 months.For further information about the conduct of the trials consult:

LA Koutsky,KA Ault and CM Wheeler et al

A controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine

New England Medical J (2002) 347 (pp1757-1765DM Harper,EL Franco and C Wheeler et al

Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with HPVtypes 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial.

Lancet (2004) 364pp1757-1765A NEW VACCINE AGAINST HUMAN PAPILLOMAVIRUSES

Gardasil* is a new vaccine which is being marketed by Sanofi Pasteur/ Merck and Co in Europe as the worlds first anti cervical cancer vaccine. The vaccine is designed to prevent infection with the genital human papillomaviruses (HPV types 6, 11, 16&18) which are the commonest cause of genital warts and cervical cancer. In large scale clinical trials of the vaccine, women aged 16-23 who did not have HPV infection before the trial, were still free from infection with HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18 after five years and none had developed precancerous or cancerous changes in the cervix.The vaccine was approved for clinical use by the American Food and Drug Agency in June 2006. A few months later, the European Medical Agency (EMEA) granted a licence for use of the vaccine in the 25 countries of the European Union. Other countries which have approved the use of Gardasil include the Canada, Mexico, Brazil, Australia and New Zealand.

Since genital infection with human papillomaviruses is a common sexually transmitted disease, it is advisable for girls to be given the vaccine before they become sexually active. Thus for maximum efficiency injections of the vaccine should be given to young girls and adolescent females before exposure to HPV. This protocol was endorsed by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and EMEA and other national agencies. In fact, the American Advisory Committee on Immunisation Practices (ACIP) went so far as to recommend that Gardasil be placed on the childhood immunisation schedule of schoolgirls at the 11-12 year old visit.

The reaction of health care providers, politicians, women’s groups and other interested groups to the new vaccine has been very variable. In November 2006, the Australian government announced free vaccination to all 12-26 year old females in 2007. A similar measure has been approved by the German government. In the USA, 20 states drafted legislation in support of compulsory vaccination of schoolgirls aged 10 - 12 years. This has met with strong opposition from health care workers, politicians and women’s groups who consider it an infringement of parental rights. Others object to vaccination of adolescents against a sexually transmitted disease on the grounds that it will promote promiscuity.The ethical issue surrounding the administration of the new vaccine are but one of the problems associated with Gardasil. Gynaecologists and health care workers are concerned that the vaccine has been insufficiently tested for long term side effects and the duration of protection against infection with HPV6, 11, 16, 18 is not yet known.

Long term studies are needed to determine whether vaccination alone can protect against cervical cancer. Merck and Co who developed the vaccine, acknowledge that the vaccine can only provide protection against 70% of all cervical cancers and a vaccine that can protect against all HPV types associated with cervical cancer presents a major challenge.Although Merck and Co make it clear that women who receive the vaccine should continue to have regular Pap tests, there is concern that after vaccination women may acquire a false sense of security and fail to attend for a check up. Serious omissions from all the discussions that have raged around the introduction of the vaccine, is a clear and concise statement that there is need for continuous monitoring and follow up of all individuals who have been vaccinated. In addition a register of all recipients of the vaccine should be maintained.

IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention ()

Volume 10 Cervix Cancer Screening

Chapter 1:pp26-45 Aetiology of cervical cancer

Szarewski A. Prophylactic HPV vaccines. [Review] [47 refs] [Journal Article. Review] European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 28(3):165-9, 2007.

UI: 17624079JAMA. 2007 Aug 15;298(7):743-53. Navigation to comments in

JAMA. 2007 Aug 15;298(7):805-6. Effect of human papillomavirus 16/18 L1 viruslike particle vaccine among young women with preexisting infection: a randomized trial. Hildesheim A, Herrero R, Wacholder S and others